Hello my friends

I'm very happy you are visiting!

Hello my friends

I'm very happy you are visiting!

Saturday was another re-entry day.

Pick up the dry cleaning.

Gas up.

Need a fowl and veggies to replenish my chicken stock.

Need some wines.

Need a new water purifying and sparkling system.

A set of car trips today.

What a hoot if the gosh-darned car doesn’t start.

Today is Sunday, September 30, 2018

This is my 173rd consecutive daily posting.

Time is 6.04am.

Boston’s temperature is 68* and the weather will be sunny.

__________________________________________________

I liked Chicago.

Would definitely go back.

Here are some street scenes showing nifty buildings and an active street scene.

_____________________________________

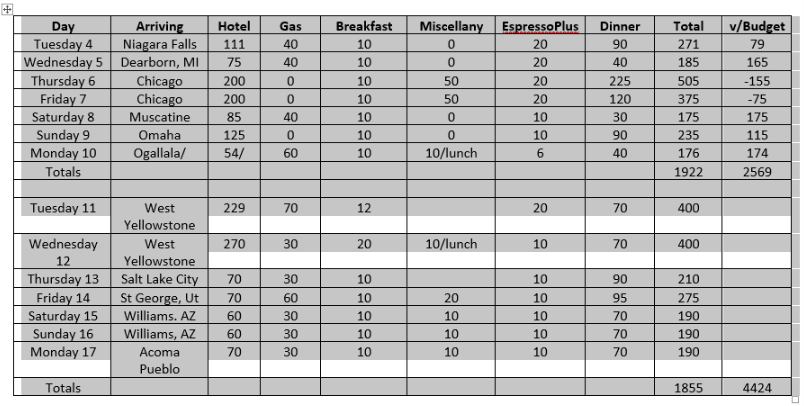

How much did the trip cost?

______________________________________

I did not keep a grocer’s figures with list after list.

Every figure is approximate.

But the upshot is that the trip cost 9923+ for 23 days, or $431 per day.

My original guess was 11,000 for 30 days or $367 per day.

Looks like I was off the mark.

The lodging estimate was likely the cause.

I don’t think it was food.

While I had some expensive dinners, I had more inexpensive dinners than I bargained for; than I wanted.

But overall, since I kept reducing the length of the trip as I went along, the trip ended up being a full 7 days shorter than projected so the actual expenditure was $1000 less than budgeted.

And that’s a two-edged sword.

On to the next one.

First thought: a week under the Tuscan sun.

Needing time to plan for it; to save for it.

Projecting early June, 2020.

The Agnew Clinic depicts Dr. Agnew performing a partial mastectomy in a medical amphitheater.

He stands in the left foreground, holding a scalpel.

Also present are Dr. J. William White, applying a bandage to the patient; Dr. Joseph Leidy (nephew of paleontologist Joseph Leidy), taking the patient's pulse; and Dr. Ellwood R. Kirby, administering anesthetic.

In the background, the operating room nurse, Mary Clymer, and University of Pennsylvania medical school students observe.

Eakins placed himself in the painting – he is the rightmost of the pair behind the nurse – although the actual painting of him is attributed to his wife, Susan Macdowell Eakins.

The painting, also, records the significant transition, in just 14 years, from the earlier status quo – the participants' black frock coats represented in The Gross Clinic (1875) – to the "white coats" of 1889.

The painting is Eakins's largest work.

It was commissioned for $750 (equivalent to $20,428 today) in 1889 by three undergraduate classes at the University of Pennsylvania, to honor Dr. Agnew on the occasion of his retirement.

The painting was completed quickly, in three months, rather than the year that Eakins took for The Gross Clinic.

Eakins carved a Latin inscription into the painting's frame.

Translated, it says: "D. Hayes Agnew M.D. Most experienced surgeon, clearest writer and teacher, most venerated and beloved man."

The work is a prime example of Eakins's scientific realism.

The rendering is almost photographically precise – so much so that art historians have been able to identify everyone depicted in the painting, with the exception of the patient.

It largely repeats the subject of Eakins's earlier The Gross Clinic (1875), seen at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The painting echoes the subject and treatment of Rembrandt's famous Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) (in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague, the Netherlands), and other earlier depictions of public surgery such as the frontispiece of Andreas Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica (1543), the Quack Physicians' Hall (c. 1730) by the Dutch artist Egbert van Heemskerck, and the fourth scene in William Hogarth's The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751).

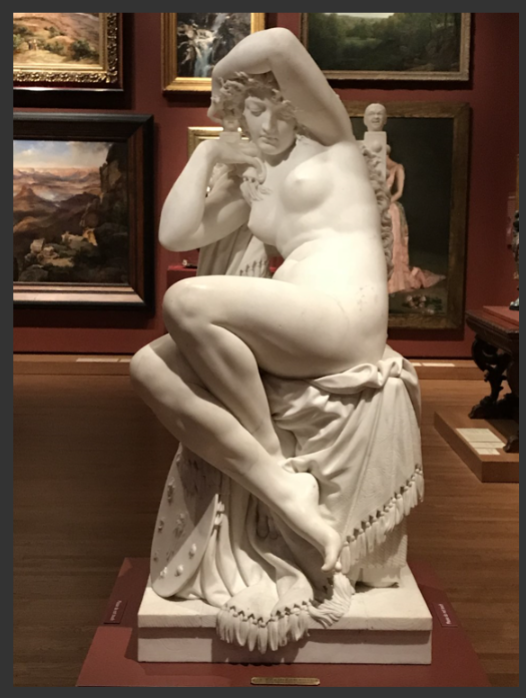

Howard Roberts (sculptor) (April 8, 1843 – April 19, 1900) was an American sculptor based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

At the time of the 1876 Centennial Exposition, he was "considered the most accomplished American sculptor."

But his output was small, his reputation was soon surpassed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens and others, and he is now all but forgotten.

Examples of his work are in the collections of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the U.S. Capitol.

Born into a well-to-do Philadelphia family, Roberts studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts under sculptor Joseph A. Bailly.

He was an exact contemporary of fellow Philadelphian Thomas Eakins, and both entered the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1866, and studied under sculptor Augustin-Alexandre Dumont.

Eakins did not consider Roberts a friend, calling him "a rich disagreeable young man from Philadelphia, one who has without any apparent reason seen fit to be my enemy."

Still, Eakins may have sketched him, and Roberts brokered a reconciliation between Eakins and Mary Cassatt.

Roberts continued his studies under sculptor Charles Gumery, before returning to Philadelphia in 1869.

Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the first of seven children.

His middle name commemorated the struggle at Osawatomie between pro- and anti-slavery partisans.

His father Benjamin Tucker Tanner (1835-1923) was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent black denomination in the United States.

Being educated at Avery College and Western Theological Seminary in Pittsburgh, he developed a literary career.

In addition, he was a political activist.

His mother Sarah Tanner was born into slavery in Virginia but had escaped to the North via the Underground Railroad.

She was mixed race, and Tanner himself was either a quadroon or an octoroon.

The family moved to Philadelphia when Tanner was young. There his father became a friend of Frederick Douglass, sometimes supporting him, sometimes criticizing.

Tanner is often regarded as a realist painter, focusing on accurate depictions of subjects.

While works such as The Banjo Lesson were concerned with everyday life as an African American, Tanner later painted themes based on religious subjects, for which he is now best known.

It is likely that Tanner's father, a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, was a formative influence for him.

Tanner's body of work is not limited to one specific approach to painting and drawing.

His works vary from meticulous attention to detail in some paintings to loose, expressive brushstrokes in others.

Often both methods are employed simultaneously.

The combination of these two techniques makes for a masterful balance of skillful precision and powerful expression.

Tanner was also interested in the effects that color could have in a painting.

Many of his paintings accentuate a specific area of the color spectrum.

Warmer compositions such as The Resurrection of Lazarus (1896) and The Annunciation (1898) express the intensity and fire of religious moments, and the elation of transcendence between the divine and humanity.

Other paintings emphasize cooler, blue hues.

Works such as The Good Shepherd (1903) and Return of the Holy Women (1904) evoke a feeling of somber religiosity and introspection.

Tanner often experimented with light in a composition.

The source and intensity of light and shadow in his paintings create a physical, almost tangible space and atmosphere while adding emotion and mood to the environment.

Tanner also used light to add symbolic meaning to his paintings.

In The Annunciation (1898) the angel Gabriel is represented as a column of light that forms, together with the shelf in the upper left corner, a cross.

This view of the representation of Gabriel is consistent with James Romaine's comment that "Through the visual language of her pose and expression Tanner draws the viewer into Mary's inner life of virtue, trepidation, acceptance, and wonderment."

Mary's acceptance includes her acceptance of the cross that she will have to bear by consenting to be the Lord's handmaid (Luke 1:38).

That’s it for today, my friends.

Be well.

Love you.

Dom