Hello my friends

I'm very happy you are visiting!

Hello my friends

I'm very happy you are visiting!

Except when you are in Ogallala.

The Black Hole of nothing to-dos.

The graveyard wherein elephant-sized ‘nothing-to-dos’ go when they die of boredom.

Whence they lure dull humans to death-by-nothing-to-do.

So it was that that exception caused me to I violate my newly adopted purpose of limiting my travel.

or hundreds of miles I drove past nothing-to-do.

When I got to Ogallala I despaired with nothing to do.

Then I discovered that driving west, I had gained an extra hour in the day. Yayy!

An extra hour of nothing to do. Boo!

Then dumb me got an idea.

Too late to cancel the room at the Super 88, I took the room but brought only the laptop in with me.

I looked up Cheyenne.

At 175 miles distant, a reach after driving 315.

But it’s 3.00pm.

The speed limit is 80.

Traveling at 77/78 for me?

v nothing to do?

I will lie down and rest for 20.

Wash up.

Use the john.

And go.

And I did.

Stopping at every rest stop.

Driving safely.

I did.

And driving, I imagined.

That I poured one of those nips I had packed.

Over ice.

Sipping slowly.

Amazing company, the cup.

Smiling as we interacted.

Driving slightly under the speed limit.

The last suck 45 minutes later and 60 miles closer.

But the glow lasting the entire 175.

Plus the glow from the setting sun.

Painted everything orange.

Cheyenne here we come.

With a smile on.

So sue me.

Got to Cheyenne easily, and did nothing but eat a mediocre Japanese dinner.

Should have done nothing.

________________________________________

Today is Wednesday, September 12, 2018

This is my 155th consecutive daily posting.

Time is 5.12am and the weather will be 63 and partly cloudy.

Last night I ate a bison steak, well-prepared at ‘rare,’ an delicious.

Feeling the pressure of the road.

When will it turn from nothing to see or do to the Wyoming of Yellowstone?

_____________________________________________

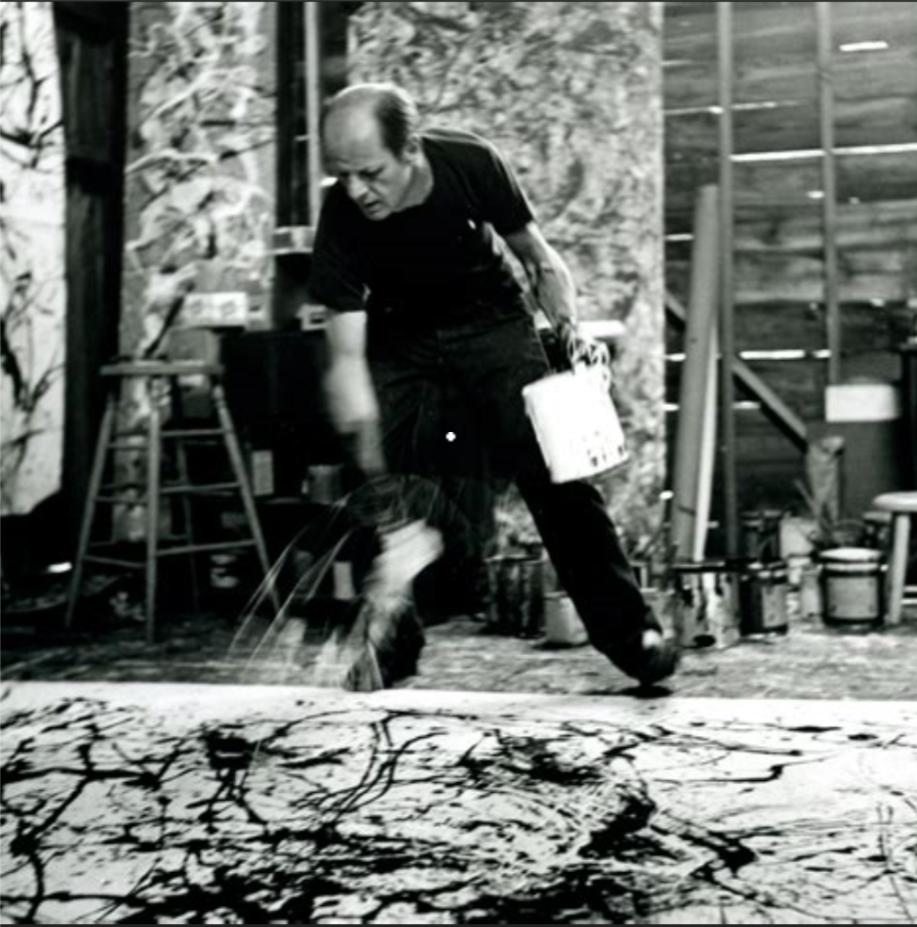

Let’s continue with a bit on Jackson Pollack.

Greyed Rainbow

Paul Jackson Pollock (January 28, 1912 – August 11, 1956) was an American painter and a major figure in the abstract expressionist movement.

He was well known for his unique style of drip painting.

During his lifetime, Pollock enjoyed considerable fame and notoriety; he was a major artist of his generation.

Regarded as reclusive, he had a volatile personality, and struggled with alcoholism for most of his life.

In 1945, he married the artist Lee Krasner, who became an important influence on his career and on his legacy.

Pollock died at the age of 44 in an alcohol-related single-car accident when he was driving.

_____________________________________________

Don't forget to communicate with me @

domcapossela@hotmail.com.

Victor Passacantilli did.

Dom,

I am enjoying your quotidian journal. You and Howard are affording me an opportunity for conjuring up all the wonderful vocabulary I began learning at Boston Latin School.

Stay well and safe,

Victor

Web Meister responds: I had to look it up: “of or occurring every day; daily”

Cute, my friend.

___________________________________________

So now it’s Howard’s turn.

Sashimi Dinner #3

Order

Design

Composition

Tone

Form

Symmetry

Balance

More red...

And a little more red...

Blue blue blue blue

Blue blue blue blue

Even even...

Good...

Bumbum bum bumbumbum

Bumbum bum…

More red...

More blue...

More beer...

More light!

Color and light

There's only color and light

Yellow and white

Just blue and yellow and white

Look at the air, miss

See what I mean?

No, look over there, miss

That's done with green...

Conjoined with orange...

—Stephen Sondheim, “Color and Light,” from “Sunday in the Park with George”

In that great mythology of the self with which we burden our subconscious, we are like the heroes of an ancient Greek epic. Adorning ourselves with self-appointed epithets of valor, during the course of our lives we accrue certain attributes like the swift-footed Achilles, or the brave Ulysses of Homeric tales. Not to suggest that these qualities dog us top-of-mind – or in any way consciously – during the flow of our quotidian.

In moments of stress, perhaps in moments, now so rare, of quiet contemplation, we may comfort ourselves with thoughts of the more sterling of our virtues. Or, depending on the nature of the moment, we may suddenly find ourselves confronting our baser degraded nature: the less noble of what we shamefully confess as our faults to ourselves, if no one else: those things we insist we shall correct before we die. For sure we all mean to reconfigure our selves in the course of time into better and better creatures.

In the meantime, as best we can, we joust with our enemies, and wrestle our demons. And maybe we, in those moments of the secret contortions of doubt and that rare sense of worthlessness that threatens to topple our sense of balance we falter. When the equilibrium that permits us always to move forward on the currents of existence wobbles, we feel that somehow our fate has been mysteriously, but above all incomprehensibly, cast into the depths.

In now ancient habits of perception we speak of fortune “not smiling upon us” at those times. And the chief challenge is somehow to find the way, a method, or a strategy, a tactic, some deft set of moves, that will resurrect our spirits and set us once again confidently on our usual path forward. If not, strictly speaking, upward as well. Of course it is.

To the ancients in fact, as part of the cosmology, fortune was not an abstraction, formless and indistinct. They imagined a god or, often in the case of Fortune, as a goddess – and not some inchoate force or tendency of the universe, but a being purely existential, and embodied, like many other incomprehensible forces with no corporeality or substance in our world of solids and flesh, of reality. Perhaps it was because of the very fickle nature of the ways and acts of Fortune, raising some up even as she cast down others, that ascribed this indubitably unfair gendered identity on this capricious deity. But whatever the reason, and however unreasonable its ascription, there was no doubting the actions she imposed on humans.

The trope was powerful and basic and universal. Fortune puts us on a great wheel, and turns it. The ferris of Fortune. So, with each revolution, some were raised up, to view the landscapes of life, if not of the firmament as well, from the highest vantage, even as others were lowered, down and down, perhaps to tumble off the wheel on the hard surface of a too too solid earth. With such a view of human prospects at the hands of such a mercurial deity, philosophy evolved with a predictable tone or cast.

How often do we believe we will not merely tempt the fates, but overcome or outsmart them – if not, more humbly, somehow merely even out the odds? Some regimen, or regular habits of being, any actions other than the unwavering and unresisting submission to the vagaries of existence seemed likelier to be redemptive. And, indeed, it seemed to work for some. Except when it didn’t.

An old saying, in one form or another, has persisted since those days of antiquity. The Greeks and Romans embraced the notion of defiance. “Fortune favors the bold,” is how it goes, or the “brave” or the “strong.” You get the gist. Words to that effect are what Pliny the Elder is recorded to have said to his nephew, also Pliny – Pliny the Younger – as the older gent set sail in his fleet to inquire into this Vesuvius business; eruptions, destruction. He was helping a friend. He lost his life in the undertaking.

We call that irony. However even if we do not call it that, there is an inescapable fact, not ineluctable for each of us with regard to ups and downs, except that we are all doomed eventually to prove our mortality. The fact is, irrespective of how we choose to conduct ourselves, fortune will reign as it will. And the virtues of boldness or resolution, or strength or courage may have value, but not by way of altering the unpredictability of the specific course of our lives.

_____________________________________

In 2002 my wife Linda and I managed to realize a dream we shared over the course of the first ten years of the life we had agreed to have together. We bought a medieval maison de village in a tiny hilltop hamlet deep in rural Provence. In February of that year we accepted title in the office of a French official, a special kind of lawyer, called a notaire. We proceeded from the legalities immediately to begin to furnish our new second abode. We visited again in the warmer months, for a longer stay, and commissioned some needed repairs and remodeling to be done, and returned home to spend an uneventful fall and a chilly winter in Boston.

In January of the new year, she was diagnosed with a relatively rare form of breast cancer, hard to identify and almost indistinguishable from other common ailments that are eminently treatable. It can only be diagnosed by biopsy, and by the time taking such measures seems prudent it is usually well advanced, and requires radical treatment. Inflammatory Breast Cancer, so-called because it masquerades as an infection, it turns out is one of the most aggressive forms of the disease, and is indiscriminate as to age of the victim.

Nine months later, after chemotherapy, radical surgery, a recuperative holiday in our beloved French village, and then a course of radiation, Linda was well enough to return to work, which she did. Then, in October, during a routine colonoscopy another cancer was discovered, completely unrelated and requiring the initiation of a separate course of treatment. Because the cancer had already metastasized to her liver, she was scheduled for two more major surgeries – the first, highly successful, prior to the start of chemotherapy, and the second, seemingly successful at first. Its complications persisted through the remainder of her life. Why did she get two cancers, unrelated? According to her oncologist (well, one of them, and he a world-famous clinician and researcher of breast cancer), “bad luck.” No more. No less.

We endured together, for five and a half years. I cooked our meals. I cleaned her constantly draining wound from the liver surgery (which cost her ⅔ of that organ, but prolonged her life). I injected. I swabbed. I bandaged. I took voluminous notes of every consultation. I kept the world of her numerous friends and relatives abreast of her condition. I arranged our travel. And did all the driving, across town, or across Provence, as we made numerous trips. And, to our surprise only once, the first time we asked, her doctors always assented to the idea of another visit to our serene paradise.

Linda worked until she couldn’t. Her employers, IBM, were magnanimous and accommodating. Money was never a problem. Insurance was never a problem. There was never a problem, except for what stared us in the face every morning when we woke up, and it was the same world with the same prospects. And there was no sense there was anything bold, or brave, or strong, or noble, least of all, about how we conducted our lives.

Early on, she had said, I am still me (and she was, minus some parts in time, and a couple of times, minus her luxuriant hair, which always grew back, though greyer each time, and curly or straight as the whims of the hair gods willed it). I am not going to be defined by a disease. And she wasn’t. Two weeks before she died, she was out until one in the morning, because a friend, the widow of a colleague, a subordinate of hers who had died of cancer a year before, had scored tickets to the playoffs for the Celtics. And would she like to go? Are you kidding? She tried not to wake me up when she got home. Almost made it.

We went to France right afterward. And yes, these latter trips required the hire of a wheel chair (fauteuil roulant) on the other side, but she eschewed its use unless absolutely necessary. Usually walking up the stubborn hills on which the whole province is built.

On the day we were packing to leave for Nice, to take the first leg of our usual route back to Boston, her legs wouldn’t support her, and she collapsed to the floor, very slowly. Twice. “That’s funny,” she said, “that’s never happened before.” I helped her into our bed, freshly made, in anticipation of some future return, and I called the EMTs.

In France, ambulances under such circumstances arrive with a doctor on the team, and they made short work of determining she had to be transported to the local hospital. I followed them in our rental car. She was admitted. And I drove on to Nice to drop off a friend who had been visiting with us, to assist somehow, though never clearly how, and who was nervous about making her connection to Italy. I drove back to Draguignan, and saw Linda, now admitted to a private room in the ICU connected to the emergency service. She was sitting up and eating apple sauce, and very tired. I said I’d go home and change and eat something, and return to spend some more time with her. But she demurred and said there wasn’t much point, as she was going to crash for sure, and she’d see me in the morning. I kissed her and said good night, and that was the last time I saw her conscious.

The hospital woke me the next morning at 6am and informed me her organs were failing and to come back to the hospital as soon as it was convenient. I spent that day, contending with my halting French, trying to help resolve the question as to whether she was sufficiently stable to be medivaced back to Boston. Suffice it to say she wasn’t. The physicians speaking for the insurance company wouldn’t have it.

I slept in her room that night, trying fitfully actually to sleep in two chairs pulled together seat cushion to seat cushion, with my ears stoppered with ear pods and the Beatles faintly playing, mainly drowned out by her struggle to breathe. She died with me alone in the room with her at 5:45 the next morning.

I wasn’t able to return until a week later, her cremated remains installed in a place of honor in our little house, and utter uncertainty about anything leaving my mind blank, and my path forward equally uncertain. All I knew about Linda, after speaking long distance to her oncologist at Dana-Farber was that it was amazing she kept going on her own steam for all but the last two days of her life. “Her body was totally full of cancer for the last two years,” he said. All they could do, which they did, was keep it at bay, and keep her out of pain. For those last few weeks, she walked around with a crack in her pelvis, because the bones had been so weakened by radiation they couldn’t stand up to the cancer in them.

________________________________________

When I got back home, my life and attention were completely filled with the administrative demands of tending to her affairs and her estate, and my own meager business matters.

Tending to myself was easy enough. I had long since learned, during her long decline, that unless she was at home, I never saw the need to prepare and cook meals for myself. And I lost the habit of doing so. It was simply less demanding either not to eat, or to satisfy the rare pangs of hunger by going out. I was a ten minute walk from some superb places to eat in our neighborhood of Harvard Square. And there were bars, which sometimes held a greater allure for the usual reasons.

When even the presence of other people – because after all, I was not particularly disposed to be much of a social animal – I simply stayed home and slowly enough depleted our well-provisioned stock of liquor. Not wanting to neglect my needs altogether, I would make a quick run to that paradise of hipster victuals – a super-size Whole Foods. The greatest treasure among its indulgences for those who they were more than happy literally to cater to? The sushi bar, manned, it seemed, from the moment the store opened to the time they shut off the lights, by diminutive chefs always bowed over their bamboo mats. Roll after roll.

I preferred sushi, or, even better, sashimi. It was light. It was minimal. It was the most direct intake of the food I preferred, and seemed to need. Protein. In a form that provided one step or two away from live flesh. From life itself, or so it seemed in my philosophical purview, stripped away as it was to the barest existential facts.

But more than anything else, what appealed to me, what was compelling, was the Tao of it. What was stripped away more than anything else, as in so much of the Japanese esthetic entailing food, its preparation, and its presentation, were all nonessentials. The food was raw and edible with the fingers. Utensils? None, though if you wanted to be that fastidious, nothing is more fundamental than chopsticks. And the food appeared before you, declaring some innate order, and yet bespeaking the most sophisticated if minimalistic of intentionality by way of the design of it. Everything squared up. Everything on a single plane. Spatial relations all orthogonal.

It forces order on the patterns of your mind as it scrambles to think, and escape the sheer desire to emote. All animal, you are reminded you are also human. Brutish, you are reminded that social custom and basic austere order are the the foundation of an organizing principle. That where death imposes decay and chaos, life will prevail if only through the imposition of order and balance, of symmetry, of design, and composition.

And in all of these reside the only hope for an ultimate and prevailing sense of peace.

And I discovered, that indeed, with all of that, and a shot of 90 proof whiskey, and a Tsing Tao beer to wash down the fish, I had the first inkling of a sense that rebirth is possible. And though I wasn’t quite up, I no longer despaired of being down.

—Howard Dinin. © 2018.